Galomon's Guide to Oasara, Chapter 1

Ancient History

Long ago, before our people came to the islands of Myrrhe, the lands of Oasara were occupied by two very different, very powerful races. The first and oldest were the diur, giant humanoid beings of bark and fire, living in harmony with the world around them. They have long since retreated to the most seclusive places on the continent, to the tallest mountains and deepest forests, where they are best left undisturbed.

Long after came the graai, terrible creatures somewhere between man and bird, standing upright but possessing otherwise avian features. Of course, the graai are still well known across Oasara as chaotic, destructive beings; more about them later in this guide.

The first known human kingdom was the Kingdom of Oasara, after which the continent is named. Occupying the immense Mount Ylvoruan and the surrounding lands, this ancient kingdom was brought low by the foul graai shortly before our own people settled Myrrhe. Little is known of Oasara, beyond that it was primitive and no match for the might of its enemies.

More than three and a half thousand years ago, the plains of Wyrl were split into several different tribes. But then one great man, Hadidon Andrysian the first, who is still known as the First King, brought five of these roaming tribes together. Growing up, he was always awed by the bright moon Ankualar. Whereas his own tribe, the Andrysh tribe, was named the Hyena tribe, he always wanted something more to represent his new combined tribe. So, he chose a symbol that every man everywhere could recognize, something they could look up to; the moon that had inspired him most as a child.

Like the moon, floating forever in the sky, he foresaw a tribe that could exist without end. To do this, he needed something more permanent than a moving camp. After years of searching, he stumbled across an immense hill in the middle of the plains of Wyrl. At the top of this hill, the first king began to build the city of Ankuan. The hill was named after him; the First King’s Hill; whilst the city, of course, was named after the moon Ankualar. Over the next thousand years, the Kingdom of Ankuan grew, though its influence remained concentrated around the city of Ankuan itself.

Galomon's Guide to Oasara

An Introduction

Greetings, traveller! With Myrrhe’s location between three continents, Oasara, Lequatah, and Aarhos, we have always had the luxury of staying outside the conflicts that plague the rest of the world. For those who wish to travel into the continent of Oasara, with its vast mysteries and wonders, preparation is advised. For this His Majesty King Averyl Rathrakai of Myrrhe has given me the task to make a guide to any and all who would brave the lands beyond our humble islands.

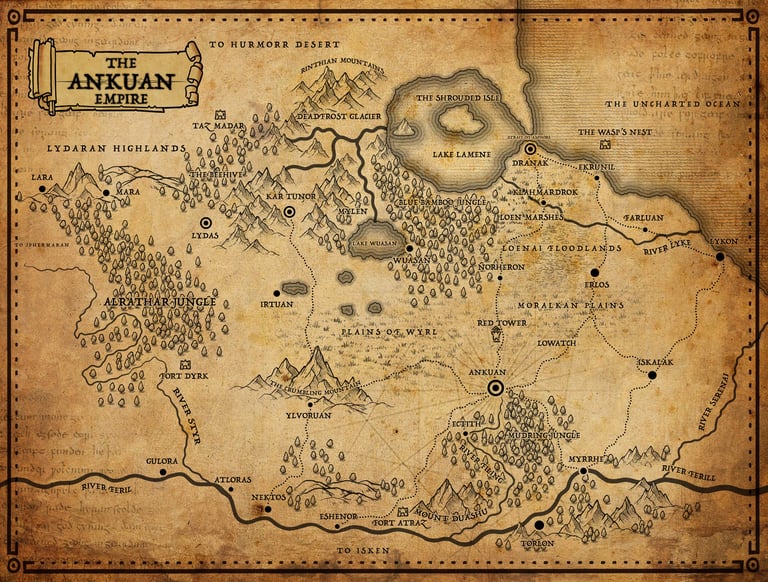

Though the borders of Oasara are a subject of debate, and the northern reaches of it unexplored, we will use the Myrrhen definition of the continent; lying between the Sea of Sariethe far to the west, the river Feril to the south, and the river Serenai to the south-east, and the Silent Ocean to the north-east. None know how far north the continent goes; only that it extends well beyond the Hurmorr Desert.

In this guide, I will tell you some of the long history of the continent of Oasara, and the forming of the single greatest human civilisation that lies upon it; the vast Ankuan Empire.

Short Story: Stolen

Neraya hated the city. The people. The noise. And how her mother always took a much longer scenic route to get home. Already at twelve years of age, she had been through the city hundreds of times. She could hear the people outside, the midday crowds, even through the carriage’s walls. And they hadn’t even reached the city yet.

Today’s journey was even longer than usual. They had come from a few leagues outside the city, where her elderly uncle lived, her father’s older brother.

‘You behaved well,’ said Lady Redara Mirandis, one of the richest women in the city, and the one who also happened to be her mother. She wore her glistening black hair in a single braid that hung over her shoulder, and she wore the dark blue kaftan that she always wore for family visits.

Neraya didn’t reply. She stared out of the window to her right. Hundreds of people travelled with them along the roads leading to the east gate, from poor farmer to rich merchant. She recognised every farmhouse they came across.

‘Why does father never visit his brother?’

She felt her mother’s eyes boring into her back, even as she kept her own eyes fixed outside, leaning out over the windowsill. The windows were closed to keep out the warmth, and still she smelt everything outside, both merchant’s wares and animal scents. She winced at a sudden shout outside, far too close for her liking. The answer she waited for didn’t come anytime soon.

‘Mother,’ she repeated.

‘They had a disagreement,’ Lady Mirandis replied, tousling her hair in that infuriating motherly manner. ‘You wouldn’t understand.’

Neraya finally turned to face her mother.

‘We have nothing else to do. Tell me.’

‘Only if you ask nicely.’

‘Please, mother.’

Lady Mirandis thought for a moment. Neraya looked out of the window again, her fingers fidgeting with a ring on her left hand. There were approaching the gates of Ankuan, though she couldn’t quite see them through the window, only the walls. If she looked at the right angle she could see the black armour of one of her mother’s household guards, walking in front of the carriage. It was also getting really hot in this carriage, and she decided she needed fresh air.

‘Your uncle should have been his father’s heir. Instead, your father became his heir.’

‘Why?’

Again, a silence from her mother.

‘Your uncle, he…he had an affair.’

‘What’s an affair?’

‘Oh. I’ve said too much already. Never you mind, Aya.’

Neraya ground her teeth. She hated that nickname.

‘You can’t not tell me now! Stop treating me like a child!’

Outside, a camel made an annoying braying noise. Neraya struck the carriage door in frustration. Her silver ring, which she had put on her forefinger, now clacked loudly against the wood.

‘Compose yourself!’ Redara snapped.

‘Only if you tell me what an affair is.’

Their eyes met. Neraya felt her cheeks redden, but her mother’s anger wasn’t expressed on her face; only her trembling hands, fingers interlaced on her lap, showed her emotions.

‘If you throw a tantrum at me, I won’t tell you anything,’ said her mother.

Neraya crossed her arms and looked out of the window again, too angry to talk. They were passing under the front gate now, and into the city. Even more noise met her, and their carriage slowed down, no doubt from all the people in the way outside.

‘Fine.’

They sat in silence for several minutes, both staring away from each other. The sun still beat down relentlessly on the black roof of the carriage, and it was only getting hotter.

‘I want to get out,’ said Neraya.

‘Now? We’re in the middle of the city.’

‘It’s too hot. I can’t breathe.’

‘We’re almost there,’ said Redara. ‘Patience.’

But Neraya had no more patience left. She’d had enough of following her mother around, sitting in the carriage half the day and listening to conversations the other half.

‘Mother, let me out.’

The carriage stopped. Redara frowned at her, then tried to look out of her window to see what had happened.

‘We can’t be there yet,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘You, stay inside!’

Redara opened the carriage door, and gracefully stepped out. There was some kind of commotion outside.

For a few seconds, Neraya closed her eyes and tried to ignore the heat. But it was too much. She opened her own door and stepped out as well.

She was met by a wave of sound. They were in the great bazaar, and she could see a sea of people to each side of her. She closed the door behind her and leant back against it, taking a deep breath. That was a mistake, because straight ahead stood a fish stall, with its wares hanging from the roof, clear for all to see. That smell alone made her nauseous.

There were several people waiting in line for it, including one with a goat by his side. But none of them were looking at the stall. They were looking at where Lady Mirandis stood, surrounded by her escort, and the obstruction blocking their way.

A pair of red-clothed merchants had driven a large wagon full of barrels out into the middle of the street, where it now leant on one corner. Neraya quickly saw the reason; one of its six wooden wheels was bent out of its shape, three of the eight spokes broken. The merchants argued vocally. One of them pointed at the wheel, as if to make a point.

‘What is this?’ Lady Mirandis demanded.

Neraya didn’t really care what was happening there. She was standing in the sun, and she needed to get to the shade. She walked around her carriage to the back, and looked at the surrounding crowd. People were streaming around the edges of the carriage, but there was still some space between her and the crowd. Some passers-by gave her disdainful looks. She was nobility, and they could all see that.

Well, she was nobility for a reason. But she had guards to protect her, all she had to do to get their attention was scream, they couldn’t do anything to her. She crossed her arms again and showed them what she thought of them with her expression.

Eventually, the space the crowds gave the cart were smaller, and soon there was little more than two paces between her and the closest commoners. She didn’t see the thief until he was holding her hand, and tearing off her ring. She was so shocked that she didn’t even stop him as he took it and ran, straight for the fish stall.

Neraya gasped. Her favourite ring! She ran after the thief, determined to catch him before he disappeared into the crowds. She was at the stall and in the crowd in seconds, and she saw the boy disappear into an alley between the houses behind the market stall.

Behind her, she heard her mother’s worried cry. That distracted her for a moment, almost stopped her, but then the rebellious part of her pushed her onwards, into the alley. She couldn’t let the ring go. When she was halfway down the alley, the boy was already at the other end of it, out of sight.

When her mother called her name again, it was faint and far away. Still, instinct told her to go back to safety. She was alone in a vast city. She had to get back to her mother.

She stopped to look at her surroundings. Clotheslines hung between the yellow walls of the sandstone houses to each side, obscuring most of what little sunlight reached here. It smelled, and there was a white cat sleeping on the ground ahead. There were also two bundles of rags to her right, and a lot of rubbish.

The rags moved. A beggar, no doubt. She had seen beggars before, but she had never been alone with one. At last, her fear caught up to her.

She began to walk back to the market, and then found two black-clothed men in her way. Both carried long, curved daggers, with serrated edges.

‘I have a knife,’ said one of them, an understatement if there ever was one. He was short and bald and had a crooked nose, and wore a golden necklace. ‘Come with me if you want to live.’

Neraya wanted to scream. But she also didn’t want to die.

‘You can’t take me,’ she replied. ‘My mother is Lady Mirandis.’

The two men shared a glance.

‘So?’ said the other man, this one much bigger and with a deeper voice to match. He had big, fleshy hands which could have held a watermelon each, and had dirt under the fingernails.

‘You think you’re better than us?’

‘Of course,’ Neraya said. ‘My mother—’

‘Wrong answer,’ said the shorter man, and took a step towards her. She turned to run, but found two more men in rags in her way. The beggars. Even as she realised it had been an ambush, she stood her ground. She wasn’t going to run now.

‘What are you going to do with me?’ she squeaked.

They didn’t reply. A bag went over her head, and her world went black. She felt herself being heaved on one shoulder by one of them, and carried away like a sack of grain.

‘Lord Grism was right,’ said someone nearby. ‘Nobility really are too arrogant for their own good.’

On the sixth day, the boy saw the hawk. Around him, the Forlorn Forest stretched endlessly. The ash-grey bark and leaves of the gedardar trees drained the world of colour, making him lose his sense of direction. Like a labyrinth without walls.

On a branch high above the boy the hawk sat, perched like a gargoyle, frozen still. Its plumage was a bright shade of turquoise, from its sleek neck to its long tail. One yellow eye scanned for movement, for its prey, but not for its hunter.

The boy didn’t move. He waited, alone, a hooded figure. Waited for it to close its eyes, look away. It looked away, and the boy took his chance, reaching for an arrow on his back. He managed to draw it, put it to his bow, all before it looked again.

A twig snapped. The hawk looked towards the sound; as did the boy. Another figure stood nearby, barely in sight.

The hawk spread its wings, and was gone.

The boy looked up to see the hawk fly away. Then he looked at the hidden figure. But it, too, was gone. He was alone.

Three days later, the boy’s supplies were running out. Water was scarce in the Forlorn Forest. Food was scarcer. He only had five strips of dried meat left.

The world was still grey, endless trees in every direction. There was no tracking a bird on the forest floor, on the bed of brown-turning leaves. He peered upward until his neck ached, until darkness began to fall. Light grey turned into dark grey, and it would soon turn to black.

Something darted past the edge of his vision. Something turquoise. He barely saw the hawk fly, near imperceptible, almost hidden by the encroaching darkness. It skimmed the ground, prey in its claws, almost swooping past the boy. He reached for an arrow, drew it, put it to the string. The hawk perched above him, tearing at its prey.

A bowstring twanged, an arrow struck the bark next to the hawk. Not his arrow. He looked for the other hunter. Saw nothing. Looked back at the hawk. Gone.

He had to find the other hunter. He ran through the forest. He was tired, but still fast. He almost missed the other hunter, camouflaged, hidden by a tree. A girl, long-limbed, short brown hair, grey cloak. Her arrow was pointed at his heart.

‘The hawk is mine, said the boy.

‘Only if you catch it,’ she replied.

‘Stop hunting it,’ said the boy. ‘Or you’ll regret it.’

The girl stared at him, bow still aimed at his chest. He could see she knew what she was doing. Turquoise riverhawks were worth a fortune, especially their bright feathers. And every hunter knew their wing-bones and spines made the best arrow shafts. He wondered if she would shoot him if he didn’t back down.

‘Drop your bow, or your arrows,’ said the girl. ‘You choose.’

He could see she was serious. But he needed the hawk. He had a debt to pay off.

‘No,’ the boy replied, and stepped behind the nearest tree. Her arrow flew, scraped his shoulder, landed in another tree-trunk, quivered in the grey bark.

His turn. He stepped out. Shot his own bow. She was running already, zigzagging from cover to cover. His arrow grazed her hip, landed on the ground further away. The boy drew his second arrow, but by then she was already too far away.

And then she was gone.

He picked up his arrow, then picked up hers. It was bone-white, and light as glass. Hawk bone. So, she had hunted hawks before, and succeeded. He had competition.

On the fifteenth day, his time was up. No more water, one last strip of dried meat. He had to find the hawk today, or die.

The world was still grey. Grey tree trunks, grey leaves on the ground. He had to look at his arms once in a while to remember there was more than terrible, boring grey. Once, a lolo tree crossed his path, its bark a stark, almost harsh white. White, even more colourless than grey. The boy touched it, the fingers of one hand trailing across the smooth surface, looking for a way past it. He knew its sap was edible, sweet, and nourishing. He looked for any crevice in the bark, any gap, to draw out the sap. He found one, put his finger to it. It had been scraped out already. How odd.

A screech sounded nearby. The boy turned to face it, and saw his quarry. The hawk was perched on a nearby rock, its eyes fixed on the boy. He couldn’t believe his luck. His hand reached, slowly, for his arrow. The hawk’s wings spread. It was terrifying up close, its wingspan twice his height, both edges scraping the surrounding trees. The boy knocked his arrow to his string.

Then he saw something else. A bird’s carcass, some kind of small, black-feathered bird. Two paces away from him. He had come between the hunter and its prey.

The hawk didn’t fly away. It flew at the boy. Suddenly, he was the prey. He raised his bow. The hawk veered upward, towards the canopy. Then dove.

The boy was afraid, but his hands were steady, and he fired. Hit its heart. Leapt aside. The hawk crashed into the ground beside him. Its body lay flat on the ground.

He had succeeded. He aimed another arrow at the hawk, circled around it, looking for movement. There wasn’t any. It was dead. So he stepped forwards, went down on one knee, and turned the hawk over with a grunt. Very dead. At last, he could go home.

‘So this is what you were here for,’ the boy muttered, looking at the carcass. ‘Your prey.’

‘No,’ said a voice behind him. A voice he recognised. ‘It was bait.’

Something sharp pressed into his back.

‘Drop your bow,’ the girl said. ‘The hawk. It’s mine.’

Short Story: Hawk Hunter

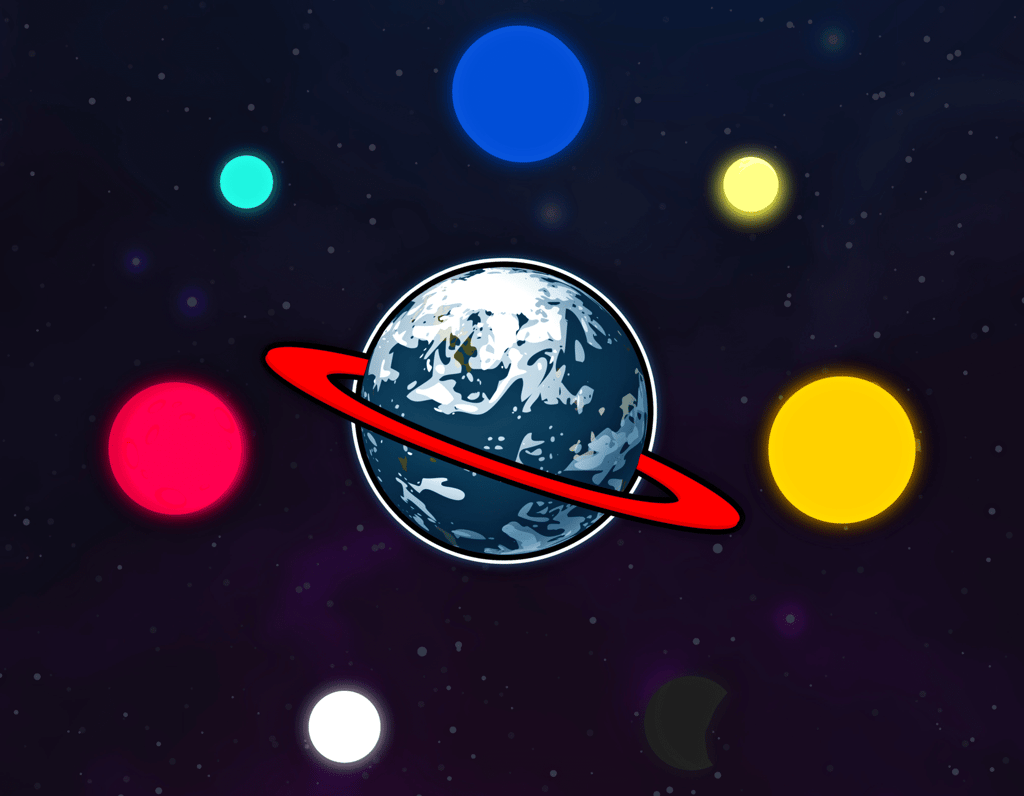

The Planet of Ishwyr

The planet of Ishwyr has seven visible moons, each playing a key role in the history and mythologies of its people. It also has the Void Ring, a great ring of red crystal, ice and dust surrounding the equator.